Table of Contents

Why 3.5% Works: The Compounding Mechanism

Last Wednesday at 10:32 PM, I was building a spreadsheet to show Lily how money grows. She's seven now, old enough to understand that the ¥10,000 I put in her junior NISA account doesn't just sit there. I wanted to show her what it becomes by the time she's 60.

I made two columns. The first showed what happens if you save ¥100,000 every month for 30 years without any growth. Just addition. The second showed the same ¥100,000 monthly with 7% annual returns.

The first column: ¥36,000,000. The second column: ¥117,000,000.

I stared at the screen. An ¥81 million difference. Same monthly contribution. The only variable was whether the money compounded or just accumulated linearly.

My wife walked past and glanced at my laptop. "What are you working on?"

"Trying to explain compound interest to Lily."

She looked at the numbers. "Did you know it would be that big of a difference?"

I realized I didn't. Not really. I'd known intellectually that compound interest was powerful. I could recite the formula. But until I saw ¥36 million next to ¥117 million, both from the exact same monthly contributions, I hadn't truly understood what exponential growth meant.

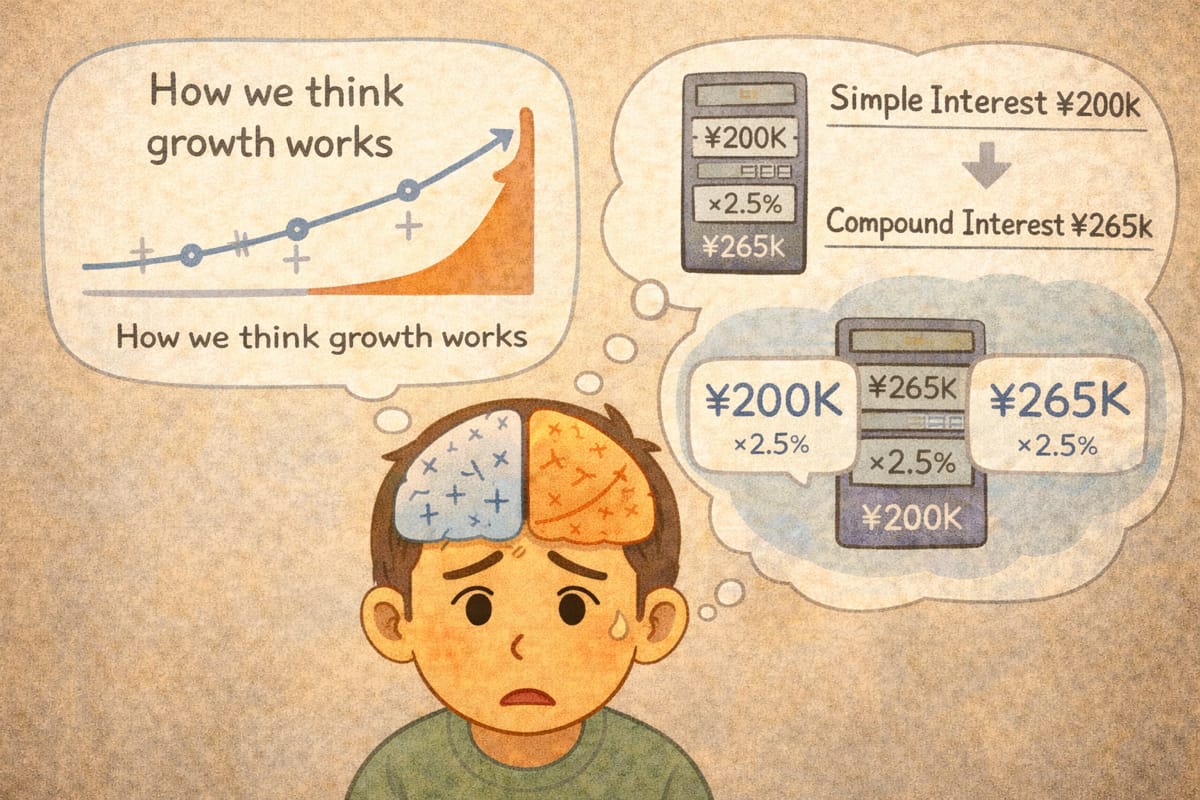

I'd been thinking about compounding linearly. And according to research, I'm not alone. About one-third of people have what behavioral economists call "exponential growth bias." We see compound interest and mentally calculate it as simple interest. Our brains flatten the curve.

That night I realized something else: the ¥81 million gap is exactly why the 3.5% safe withdrawal rate works. It's not magic. It's the compounding mechanism continuing to run even while you withdraw money.

Let me show you how it actually works.

Why Almost Everyone Gets This Wrong (Including Me)

Here's the thing: almost nobody intuitively understands compound interest. Not because we're bad at math. Because our brains evolved to understand things that grow in straight lines, not curves that accelerate.

When researchers asked thousands of people to estimate investment growth over 20 years, most people's guesses were way too low. This isn't a sign of being bad with money. It's just how human brains work. We're really good at addition. We're not naturally good at imagining growth that speeds up over time.

I'm no different. I knew the word "compound interest." I'd heard the advice to "start investing early." But until I actually built that spreadsheet and saw ¥36 million next to ¥117 million, I hadn't truly felt the difference.

It's like knowing that the sun is 150 million kilometers away versus actually feeling how far that is. The number doesn't land until you see it in context.

The moment I saw those two columns side by side, something clicked. The ¥81 million gap wasn't abstract anymore. It was real money I was either going to have or not have, depending on whether I let the compounding engine run.

Explain Like I'm Five: The Piggy Bank vs. The Magic Piggy Bank

Let me break this down as simply as possible. No percentages. Just yen.

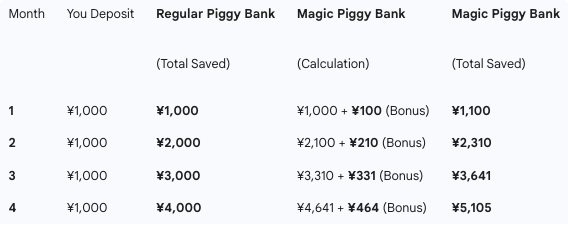

The magic piggy bank has a simple rule: For every ¥1,000 inside it, the bank adds ¥100 at the end of each month.

Regular piggy bank: ¥4,000

Magic piggy bank: ¥5,105

That's ¥1,105 extra. You put in the same ¥4,000. The difference is entirely from the magic.

Here's what makes it exponential:

Month 1: The bank added ¥100 (because you had ¥1,000)

Month 4: The bank added ¥464 (because you had ¥4,641)

Same rule. But in month 4, you had more money sitting there, so the bank added more. The magic works on everything you have, not just what you put in that month.

That's the entire secret of compound interest: Your existing balance earns money. Then that new money earns money. Then that money earns money.

This is why starting early matters. Not because you contribute more, but because you give your balance more time to grow big enough that the "¥100 per ¥1,000" rule starts producing serious yen. When you have ¥10,000,000, the bank adds ¥1,000,000. Same rule, massive difference.

Where Does the "Magic" Actually Come From?

So where does the extra money in the magic piggy bank actually come from? In real life, it comes from owning pieces of companies.

Let me back up. When you buy オルカン (eMAXIS Slim All Country), you're buying tiny pieces of about 2,800 companies around the world. Apple, Toyota, Nestle, Samsung. You own a sliver of each one.

These companies make money. And when they make money, they do two things with it:

1. They grow the business. They build new factories, hire more people, develop new products. This makes the company worth more over time. The stock price goes up.

2. They share some profit with owners. This is called a dividend. It's like the company saying "Hey, we made money this quarter. Here's your share." For the companies in オルカン, this averages about 2-3% of the company's value per year.

So if you own ¥10 million worth of these companies, they generate roughly ¥200,000-300,000 in dividends per year. That's real money the companies are paying you just for owning them.

But here's what confused me when I first looked at my Rakuten Securities account:

分配金履歴: 0円

Zero yen in distributions. No dividend deposits. No quarterly payments. Nothing.

So where did that money go?

It got reinvested automatically, inside the fund, to buy more pieces of those same companies. This is the magic piggy bank in action.

Here's what happens with simple numbers. Let's say global stocks grow about 7% per year on average (some from dividends, some from prices going up):

Year 1: You have ¥1,000,000. It grows 7%. Now you have ¥1,070,000.

Year 10: Your ¥1,000,000 has grown to about ¥1,970,000. That year's 7% growth adds ¥138,000. Compare that to Year 1's ¥70,000 gain. Same percentage, but way more yen because your base is bigger.

Year 20: Your portfolio is now about ¥3,870,000. That year's 7% growth adds ¥271,000. Nearly four times what you gained in Year 1.

This is the magic piggy bank rule playing out in real life. The same 7% growth rate produces bigger and bigger yen amounts as your portfolio grows. The growth builds on itself.

The 分配金 0円 on your account isn't a mistake. It means the fund is doing the reinvestment for you automatically, before the money ever hits your account. This matters because in Japan, if dividends come to your account first, you pay 20% tax on them before reinvesting. But if they reinvest inside the fund, you pay zero tax until you eventually sell.

Over 30 years, that tax difference alone is worth millions of extra yen.

Why Stocks Are Different From Everything Else

This is the part that finally made compounding click for me: stocks are one of the only assets where you automatically get paid just for owning them, and that payment can automatically buy more ownership.

Think about other things you could buy:

Cash in a bank: Earns almost nothing in Japan. 0.02% interest means ¥1,000,000 earns ¥200 per year. That's not compounding. That's standing still.

Gold: Might go up in price, might go down. But gold doesn't pay you anything for owning it. There's no dividend. No interest. No "magic piggy bank" rule. If you buy ¥1,000,000 of gold and it sits there for 10 years, you still just have gold. It might be worth more, it might be worth less, but it didn't generate any new gold along the way.

Real estate: The property might appreciate. But appreciation isn't the same as compounding. If your apartment goes up in value, it doesn't automatically buy you more apartments. You'd have to sell it, take the profit, and manually buy something else. That's not automatic, and it's definitely not tax-free.

Stocks (through something like オルカン): You own pieces of companies. Those companies make money and share it with you as dividends. Those dividends automatically buy more pieces. Those new pieces generate more dividends. The cycle runs by itself, forever, without you doing anything.

This is why 100% stocks, held for decades, has historically been the most powerful wealth-building approach. Not because stocks always go up. They don't. But because the compounding mechanism keeps running even when prices are flat. The dividends keep coming. The reinvestment keeps happening. The ownership keeps growing.

The 3.5% withdrawal rate works because even while you're taking money out, the remaining 96.5% is still in the compounding engine. The companies are still paying dividends. Those dividends are still buying more ownership. The engine doesn't turn off just because you're withdrawing.

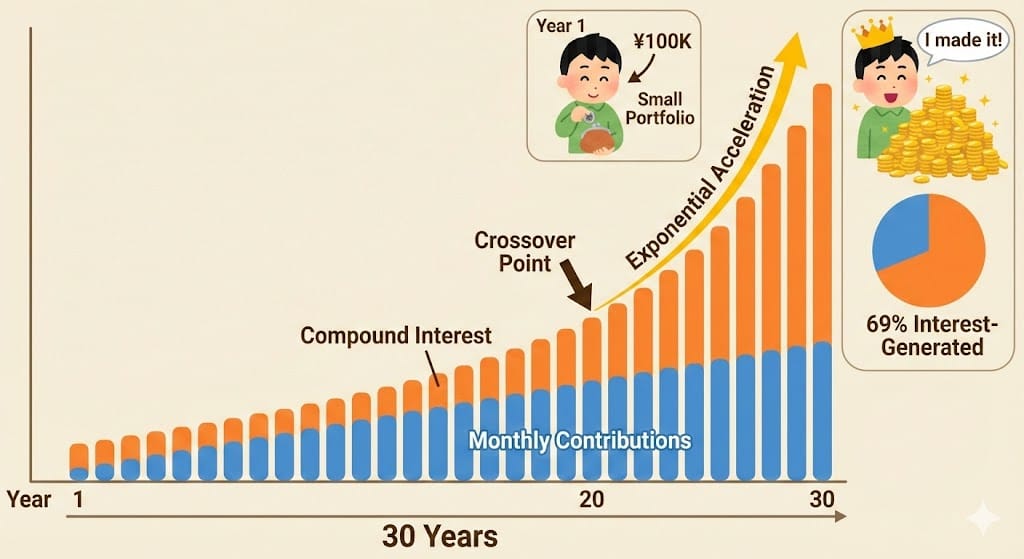

The Hockey Stick: When Interest Overtakes Contributions

The hardest part about compounding is that it feels slow for years. Then suddenly it doesn't.

I ran the numbers for the spreadsheet I was building with Lily. Monthly contributions of ¥100,000 at 7% annual return.

Then something changes.

After 20 years, contributions: ¥24 million. Portfolio: ¥52.4 million. Interest: ¥28.4 million.

For the first time, interest exceeds contributions. The money I earned on money is larger than the money I put in. The compounding engine has overtaken manual effort.

After 30 years, contributions: ¥36 million. Portfolio: ¥117 million. Interest: ¥81 million, or 69% of the total value.

This is the hockey stick. For the first 15-20 years, it feels like you're doing all the work. You contribute ¥100,000 every month and watch the balance slowly climb. The interest helps, but it's not dramatic.

Then around year 20, the curve bends. Your existing balance is large enough that the 7% annual return generates more wealth than your monthly contributions. The portfolio starts building itself.

By year 30, the compounding has done twice as much work as you did.

This is why starting early matters so much. Not because you contribute more total yen, but because you give the compounding engine more time to reach the hockey stick inflection point.

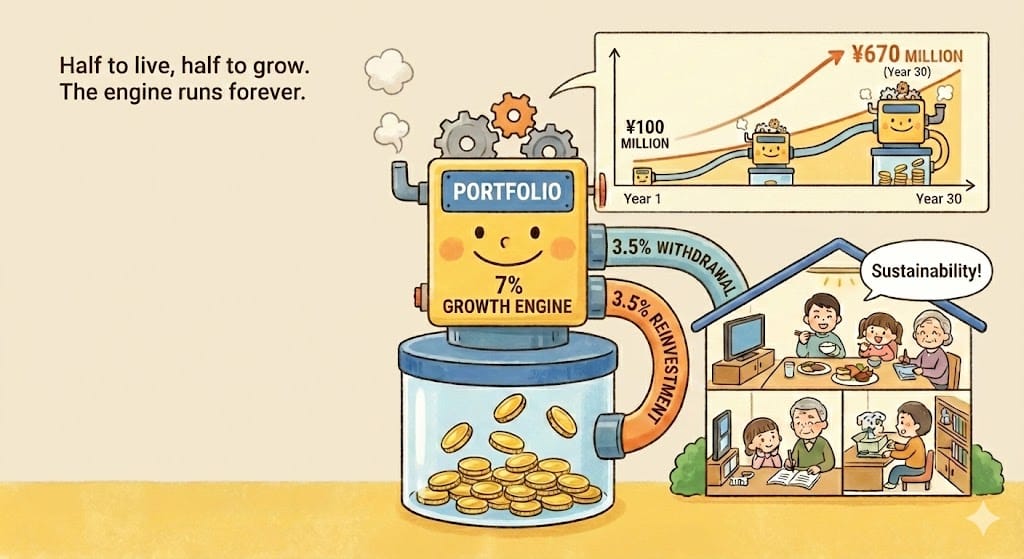

Why 3.5% Works: The Engine Keeps Running

Here's what finally made sense to me about the 3.5% safe withdrawal rate: it's not about drawing down your portfolio. It's about letting the compounding engine run at a slower speed while you take income from the excess.

The long-term average return on global equities is about 7% real (after inflation). When you withdraw 3.5%, you're leaving 3.5% in the portfolio to continue compounding.

Think about what that means with a ¥100 million portfolio:

Year 1 growth: ¥7,000,000 (7%) Year 1 withdrawal: ¥3,500,000 (3.5%) Net change: +¥3,500,000

Your portfolio grew to ¥103.5 million even after you took ¥3.5 million to live on.

Year 2 starts with ¥103.5 million, not ¥100 million. The compounding base increased. Same 7% return is now ¥7,245,000. Same 3.5% withdrawal is ¥3,622,500. Net change: +¥3,622,500.

This is why Big ERN's research found that after 30 years of withdrawing at 3.5%, the median portfolio was 6.7 times larger than it started. You didn't run out of money. You multiplied it while living off it.

The mechanism is the same as accumulation, just slower. The 96.5% you leave in the portfolio each year keeps compounding. The dividends still reinvest internally. The NAV still increases. The hockey stick still bends.

You're not depleting the portfolio. You're harvesting part of the growth while letting the rest compound.

That's the insight I couldn't see until I understood the actual mechanism: 3.5% works because the compounding engine that got you to ¥100 million doesn't turn off. It just runs at half speed, producing enough excess to fund your life while still growing the base.

🎨 Image Prompt: irasutoya-style illustration showing portfolio as engine with labeled parts, "7% Growth Engine" producing energy, split into two flows: one pipe showing "3.5% Withdrawal" going to person's household expenses with happy family, other pipe showing "3.5% Reinvestment" cycling back into portfolio base making it grow, background showing portfolio amount increasing from ¥100M to ¥670M over 30-year timeline, engine running continuously with steam/energy symbols, reassuring visualization that withdrawal doesn't deplete portfolio but just redirects half the growth.

The Cost of Waiting

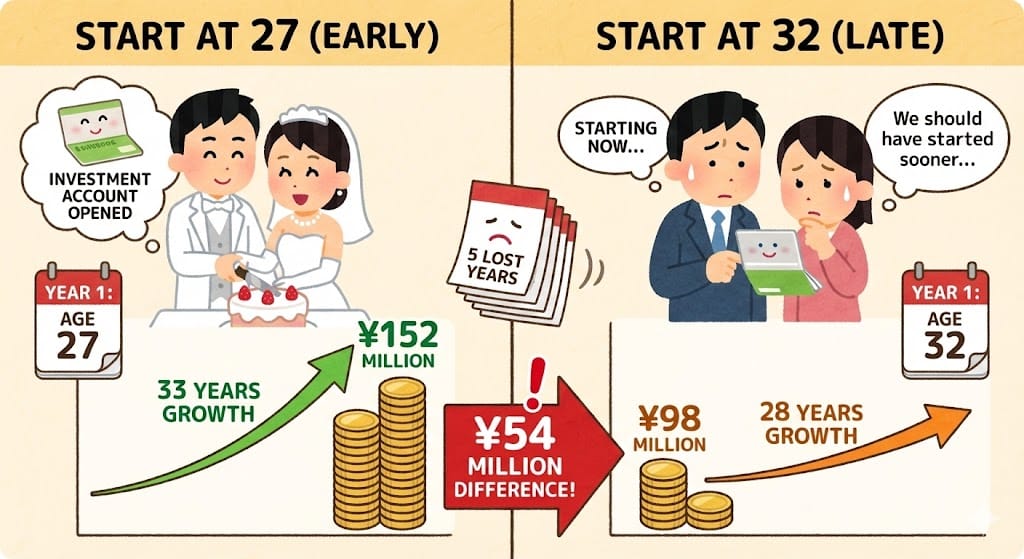

My wife asked the question that made me recalculate everything: "If we'd started investing the year we got married instead of five years later, how much difference would it make?"

We got married when I was 27. I started serious investing at 32. Five-year delay.

The math:

Starting at 27 with ¥100K/month until 60:

Years investing: 33

Total contributions: ¥39.6 million

Final value at 7%: ¥152 million

Compound interest: ¥112.4 million

Starting at 32 with ¥100K/month until 60:

Years investing: 28

Total contributions: ¥33.6 million

Final value at 7%: ¥98 million

Compound interest: ¥64.4 million

The five-year delay cost us ¥54 million in final portfolio value. Not because we contributed ¥6 million less. We did. But the real cost is the ¥48 million in lost compound growth.

Those five years from 27 to 32 would have compounded for 33 years instead of 28. The difference between 33 years of compounding and 28 years of compounding is ¥54 million on ¥100,000 monthly contributions.

I showed my wife the calculation. She stared at it quietly.

"That's more than our entire FIRE number."

It was. Our target is ¥60 million after pension integration. The five-year delay cost us nearly our entire retirement portfolio.

This is why financial blogs say "start early." But they don't usually show you the specific yen cost of waiting. When I saw ¥54 million, it stopped being abstract advice and became a visceral lesson.

We can't go back and start at 27. But we can make sure Lily starts at 2.

📋 This Week's Actions

Before next week's newsletter on bond tent strategy and withdrawal automation, ground yourself in the compounding mechanism:

Check your portfolio’s dividend history: Log into Rakuten/SBI Securities, find eMAXIS Slim All Country, look for 分配金履歴. It should say 0円. Confirm that your dividends are reinvesting internally, not being distributed and taxed.

Calculate your hockey stick year: Take your current portfolio value and monthly contribution. At 7% annual growth, when will your annual interest exceed your annual contributions? That's your inflection point. Mark it on a calendar.

Run your own "cost of waiting" scenario: If you're 35 and planning to retire at 60, calculate what happens if you wait until 40 to start. Use a compound interest calculator. See the yen difference. Use that number as motivation.

That spreadsheet I built for Lily turned into one of the most important financial realizations I've had. I thought I understood compounding. I could explain it. I knew the formula.

But I'd been thinking about it linearly. I hadn't viscerally grasped that ¥100,000 per month becomes either ¥36 million or ¥117 million depending on whether the compounding engine runs.

The ¥81 million gap is the mechanism. It's dividends reinvesting at current portfolio value, not original value. It's the hockey stick year when interest overtakes contributions. It's the reason 3.5% withdrawal works—the compounding doesn't stop, it just redirects half the growth to your living expenses while the other half keeps the portfolio growing.

This is why オルカン's 分配金 0円 matters. Why starting at 27 instead of 32 is worth ¥54 million. Why cash at 0.02% isn't "safe," it's guaranteed erosion. Why the 3.5% safe withdrawal rate isn't conservative pessimism, it's just math about exponential growth continuing during retirement.

Understanding the mechanism changed how I think about every financial decision. The question is never just "can we afford this?" It's "what's the 30-year compound cost?"

Next week: How to build the bond tent that protects this compounding engine during the critical first 10 years of retirement, and exactly how to set up 定期売却サービス to automate your 3.5% withdrawals while you sleep.

Stay Wealthy

Jason

Building wealth for English-speaking permanent residents in Japan, one story at a time.