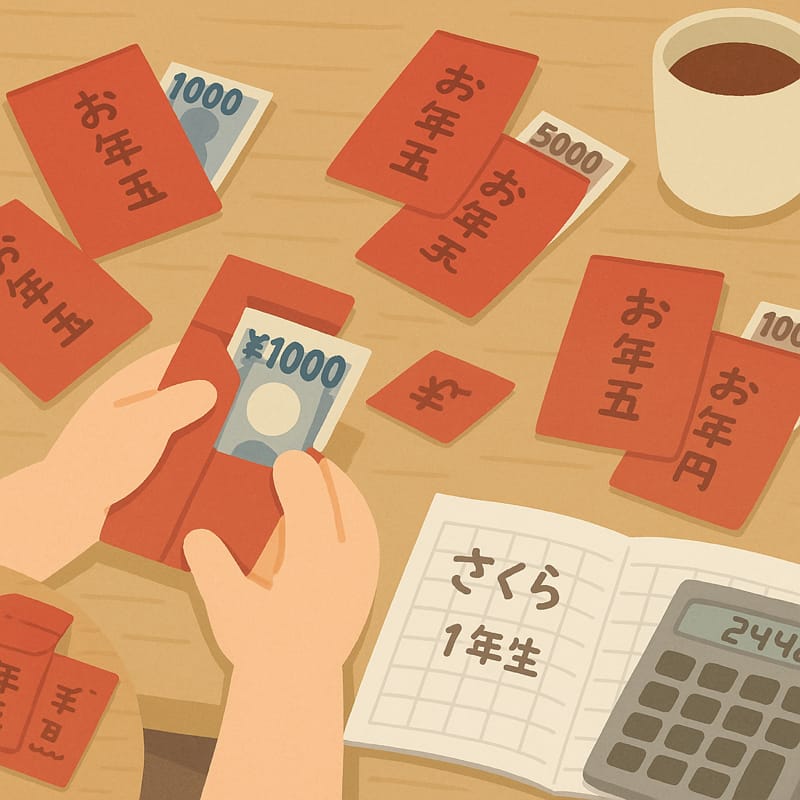

Last Tuesday morning, Lily ran up to me with a crumpled red pochibukuro from last New Year. "¥1,000, Daddy!" She can read numbers now. "Can I buy that Anpanman puzzle?"

I froze, suddenly 12 years old again in our Hong Kong kitchen, holding my own New Year money. My parents didn't say yes or no to my Pokemon card request. My mom asked: "What if we saved this for something bigger?" Then came the part that changed everything: "What would you save for?"

Even though they held the money, I had agency over the goal. That negotiation, repeated yearly with increasing percentages under my control, taught me more than any allowance could. Now, with ¥24,424 in otoshidama heading Lily's way this January (the average Japanese child receives from 5-6 relatives), I'm facing their decision: follow the 80% of Japanese parents who save it all, or teach her that agency over money matters as much as the amount?

The average elementary child receives ¥24,424 in otoshidama across three January days, following the unofficial rule: grade × ¥1,000. First graders get ¥1,000 per envelope, sixth graders ¥6,000. Multiply across 5-6 relatives and it's real money.

Here's what shocked me: 80% of Japanese parents keep all of it, saving for education. Only 20% let children manage any. The intention is responsible and very Japanese: save for university, don't spoil the child.

But my parents saved 100% of mine too. The critical difference: I chose what we were saving for.

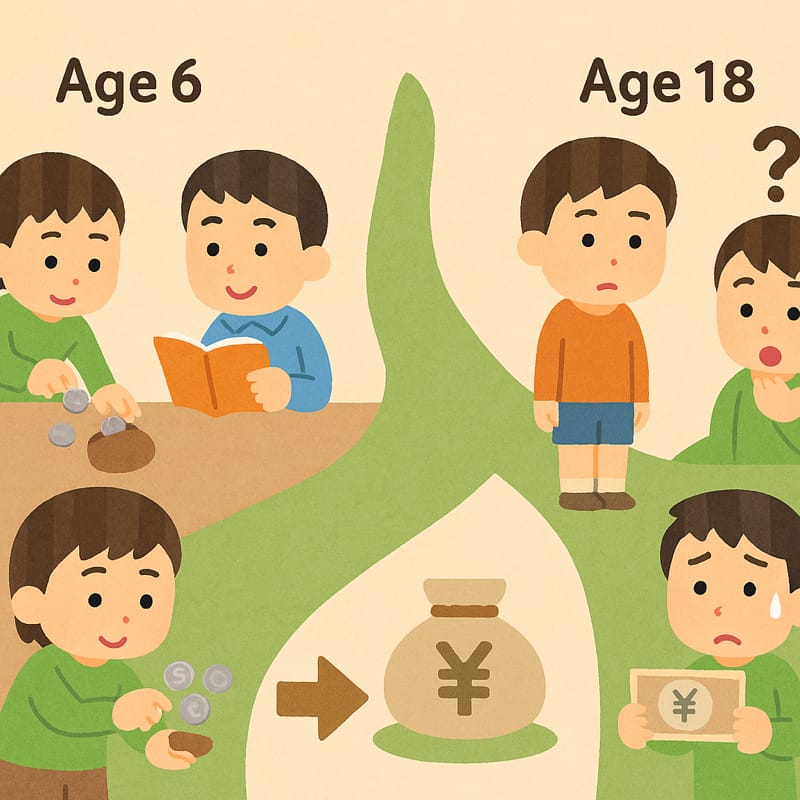

At 12, my parents offered a deal: "Control 20% this year. Show us your plan." I had ¥15,000 total. My ¥3,000 portion went entirely to Pokemon cards in one afternoon.

My parents didn't lecture. End of month: "How do you feel about that purchase?" I felt terrible. The cards had lost their novelty. I'd traded them for the ¥15,000 acoustic guitar I'd been eyeing. If I'd saved my 20% for three years, I could have bought it myself.

Next year: 30% control. I spent ¥2,000 on a game, saved ¥4,500 toward the guitar. By 15, I controlled 50%. At 17, 70%. By university, 100%, but using a system: Fundamental, Fun, Future.

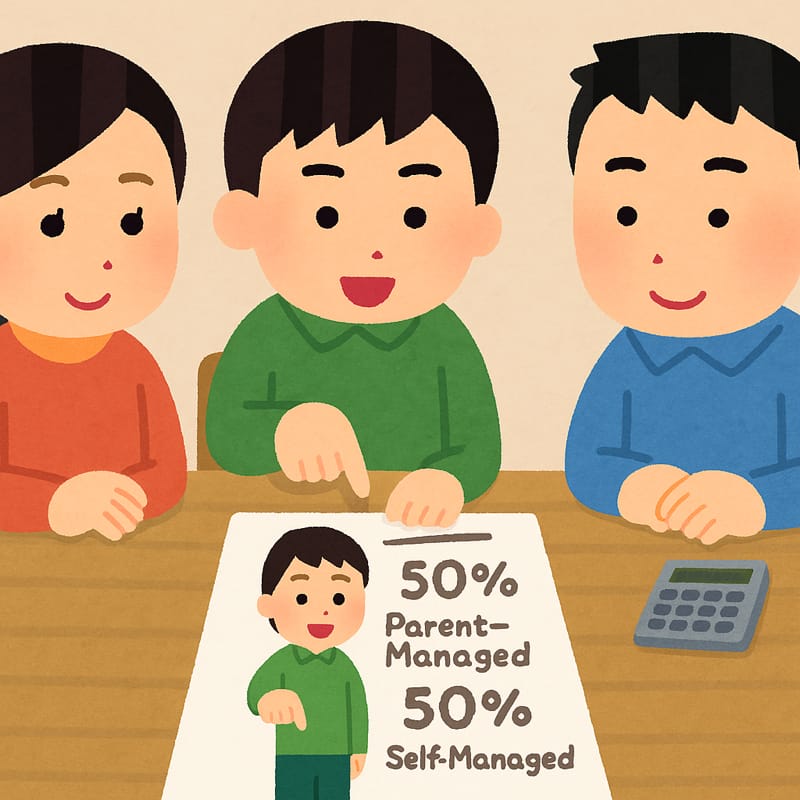

The percentage mattered less than the negotiation. Every year I presented my case. Every year they asked what I'd learned. Every year I improved at delayed gratification through experience, not lectures.

That's agency. That's what 80% of Japanese parents miss.

Here's the system I'm planning for Lily:

The Negotiated Percentage System by Age

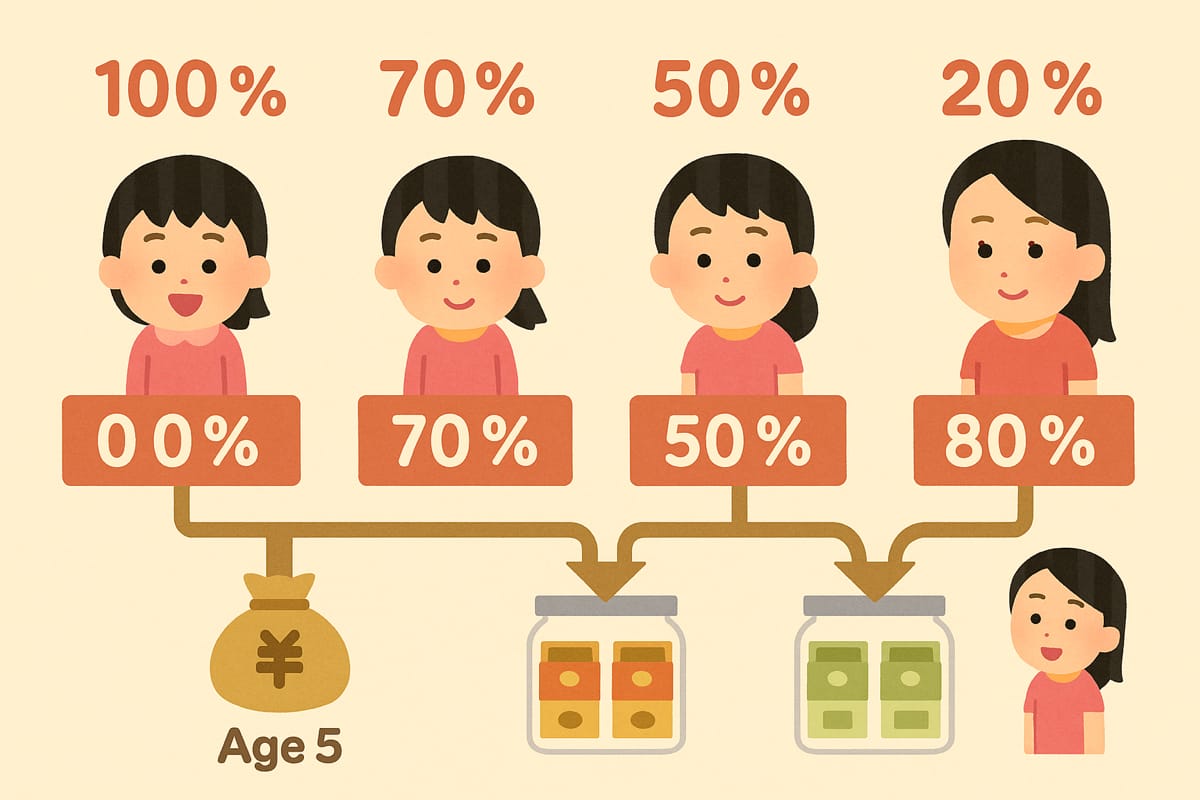

Ages 3-8: 0% financial control, 0% agency over the goal. We put all the money into her NISA account and let compound interest work it’s magic, and once kodomo Nisa is available take the tax hit to transfer into the tax free program (hopefully starting soon)

Ages 9-12: 20-30% control. Receives ¥20,000, controls ¥6,000. Must show us a plan. Can make mistakes with her portion; 70% stays protected.

Ages 13-15: 50% control. Real stakes. Receives ¥25,000, manages ¥12,500. Mistakes matter. Wins feel bigger.

Ages 16-18: 70-80% control. Preparing for university. Near-full autonomy with 20-30% still saved for education.

Every year, we renegotiate based on what she learned. She earns more control by demonstrating she can handle it.

My wife's experience was different. Her parents saved everything silently. At 18, she accessed ¥847,000, seventeen years of savings. "I spent ¥200,000 in the first month," she told me. "I'd never practiced deciding. I had no framework."

That's invisible script formation. Her parents taught her money appears in lump sums to spend immediately. Mine taught me money comes regularly, you negotiate control, you make small mistakes early to avoid large mistakes later.

We blended approaches: save the majority like her parents, negotiate control like mine. Lily's NISA account will grow, but she'll have her portion to practice with.

This January, Lily (age 2) will receive roughly ¥4,000. We save 100%, and we ask her to write down what she wants to use it for.

She chooses. We write it down. Show her the Yucho passbook. Every few months: "Remember we're saving for Disneyland? We have ¥4,000. When we have ¥30,000, we can go."

She's learning goals and delayed gratification, but not managing money yet. At five, she lacks impulse control.

What expat parents should know:

Giving amounts: Grade × ¥1,000 is socially safe. Preschoolers get ¥500-¥1,000, junior high ¥5,000, high school ¥10,000. Most families stop at age 20 or when children start working.

Reciprocity matters: Coordinate with relatives. If your child receives ¥5,000 from your sister's family, you give ¥5,000 to hers. This is why 77% of parents call otoshidama a burden.

The envelopes: Never hand bare money. Use pochibukuro (¥100-300 at konbini). 2026 is Year of the Horse. Fold money properly: face outward, thirds, front tucked in.

Bank accounts: Open a Yucho account together. Let your child see their name on the passbook, watch numbers grow. That tangible connection is part of the education.

But you can save perfectly and miss the point if your child never makes money decisions.

My colleague asked last week: "I want to save her otoshidama but also teach her. How?"

I showed him the framework. Start 80-20. Let her control 20%. Watch. Discuss. Adjust next year.

"What if she wastes it all?"

"Then she learns. Better to waste ¥2,000 at six than ¥200,000 at eighteen."

That's it: financial education costs whatever your children waste learning. Protect them from all mistakes, and they'll make bigger ones later when it matters.

The marshmallow test shows self-control is learnable through practice. Children need opportunities to choose between now and later. Ron Lieber argues avoiding money discussions makes kids obsessed with money and unable to manage it.

My parents knew instinctively: I needed agency, not just savings. Now I'm passing that to Lily, adapted for Japan, rooted in the same principle.

📋 This Week's Actions (Before January 1st):

Calculate expected otoshidama: List all relatives/friends who might give to your children. Estimate total using grade × ¥1,000 rule. Write down the number.

Decide your percentage system: Based on your child's age, what percentage will they control this year? What percentage will you save? Document your decision.

Have the goal conversation: If your child is 4+, ask "What would you like to save this money for?" Even if you're saving 100%, give them agency over the purpose.

Open a Yucho account (if needed): If your child doesn't have a bank account and will receive ¥10,000+, visit Japan Post Bank together this week. Bring your ID, your child's ID (residence card or My Number card), and your inkan or signature.

Buy pochibukuro for giving: If you're giving to nieces/nephews/relatives' children, buy Year of the Horse envelopes at a konbini or stationery store. Withdraw crisp, new bills from an ATM.

Coordinate with family on amounts: Text or call siblings/in-laws to confirm amounts you're giving to avoid awkward reciprocity mismatches. "We're planning ¥3,000 for elementary-age kids, does that work?"

At 18, Lily won't remember the exact amounts. But she'll remember the conversations. The year she wasted her portion. The year she saved six months for something and felt pride purchasing it herself. That her parents trusted her with increasing responsibility, taught her how to think about money, not just saved for her.

That framework is the real otoshidama. The cash is the teaching tool.

Otoshidama comes from toshigami-sama, the New Year deity. Families once gave rice cakes containing the deity's spirit, life energy for the year. The shift to money happened 60 years ago during Japan's boom.

The spirit remains: we give children resources to sustain and grow them. The question is whether we give just money or the wisdom to manage it.

Eighty percent of Japanese parents save all the otoshidama. Responsible. Ensuring education funds. Following the script.

But missing the negotiation. The negotiation is where learning happens.

For personalized financial guidance, please consult with qualified Japanese financial advisors who can assess your individual circumstances.

Stay Wealthy

Jason

Building wealth for English-speaking permanent residents in Japan, one story at a time.

P.S. Before January 1st, have one conversation with your child (if they're old enough to understand): "If you could save for anything, what would it be?" You'll be surprised what they say. And whatever they answer, that's your starting point for teaching agency.