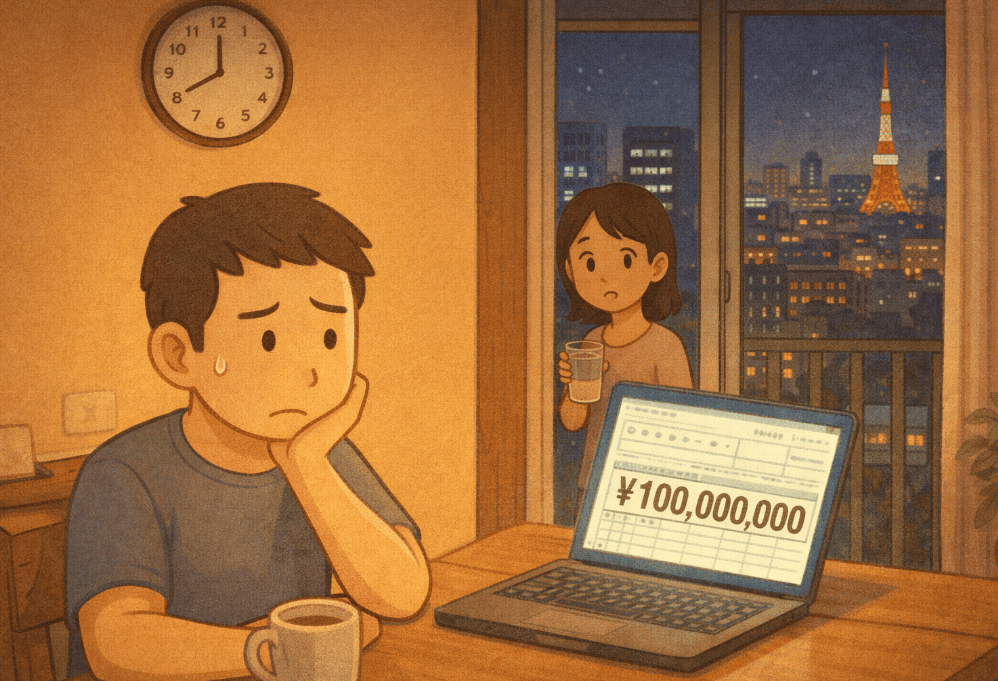

Last Thursday at 11:23 PM, I sat at our kitchen table with a spreadsheet I'd been maintaining for three years. My FIRE number glowed on the screen: ¥100 million. Twenty-five times our annual ¥4 million in expenses. Every American FIRE blog I'd read confirmed it. The 4% rule, they said. Retire when you hit 25x expenses.

My wife walked in to refill her water glass. She glanced at my screen. "How much is in your Rakuten account now?"

I checked. ¥18.2 million. All in eMAXIS Slim All Country. Up 143% since I started in October 2018.

She did the mental math faster than I expected. "So that's what, 14 or 15 percent per year?"

"About 14.5%," I said.

"And you're planning to withdraw 4%?"

I nodded.

"That seems really conservative." She refilled her glass and headed back to the living room.

I stared at my spreadsheet. She was right. My portfolio had averaged 14.5% per year. I was planning to withdraw 4%. That left a 10.5% margin. Massive cushion. Maybe I could retire earlier than I thought.

Then I remembered something I'd read on Early Retirement Now. A blog post about a retiree who started in 1966. I pulled it up.

Two hours later, I'd rewritten every assumption in my FIRE plan.

Side Note: This will be the first in a more technical series but important, and so I wanted to try make it digestible. If you have any questions reply and I am happy to clarify!

The 1966 Retiree Problem

Here's what I didn't understand until that Thursday night: portfolio growth and safe withdrawal rates are not the same thing. Not even close.

The retiree who started in 1966 retired into one of the worst periods in modern financial history. Over the next 30 years, the S&P 500 delivered solid average returns. But the safe withdrawal rate for that retiree was only around 4%. Less than half the portfolio's average long-term return.

The retiree who started in 1966 retired into one of the worst periods in modern financial history. Over the next 30 years, the S&P 500 delivered solid average returns. But the safe withdrawal rate for that retiree was only around 4%. Less than half the portfolio's average long-term return.

Over the next 30 years, the S&P 500 delivered solid average returns. But the safe withdrawal rate for that retiree was only around 4%. Less than half the portfolio's average long-term return.

A withdrawal is the amount of money you take out from your investment portfolio (typically annually) to cover living expenses during retirement, with the "safe withdrawal rate" being the percentage you can sustainably withdraw without running out of money.

The reason? Sequence of returns risk.

When you're accumulating wealth, order doesn't matter. If the market crashes 50% in year one, then rebounds, you're fine. You bought low. Your future returns make up for it.

But when you're withdrawing money every year, order becomes everything.

Imagine you retire with ¥100 million. You withdraw ¥4 million in year one (4%). Then the market drops 50%. Your portfolio is now worth ¥48 million after your withdrawal.

Next year, you need another ¥4 million for expenses. But ¥4 million is now 8.3% of your ¥48 million portfolio. You're withdrawing twice as much in percentage terms. Your portfolio has to work twice as hard to recover.

That's sequence of returns risk. Early losses combined with ongoing withdrawals create a deficit your portfolio may never escape.

I found this most clearly explained in Big ERN's Safe Withdrawal Rate Series on Early Retirement Now. He analyzed 150+ years of market data and found something that stopped me cold: "With a 4% SWR and 70-80% index funds you have a roughly 1 in 3 chance of wiping out your money after 60 years. We want the opposite: A conservative withdrawal rate (e.g. 3.25%) and a generous allocation to index funds (e.g. 100%)."

For early retirement with 40-50 year horizons, the research converges on 3.5%. Not 4%.

Wade Pfau's landmark international study reinforces this finding. He examined 109 years of data from 17 developed countries and found the optimal safe withdrawal rate for globally-diversified portfolios was 3.45%—almost exactly matching our 3.5% target. The American 4% rule, Pfau concluded, was largely an artifact of "particularly favorable" 20th-century US returns. Countries affected by wars (Japan, Germany, Austria) showed safe withdrawal rates as low as 0.47%, underscoring why global diversification matters.

For Japanese investors, this is especially relevant. Our オルカン portfolios are inherently global. We're not betting on any single country's exceptional returns. The 3.5% rate accounts for this reality.

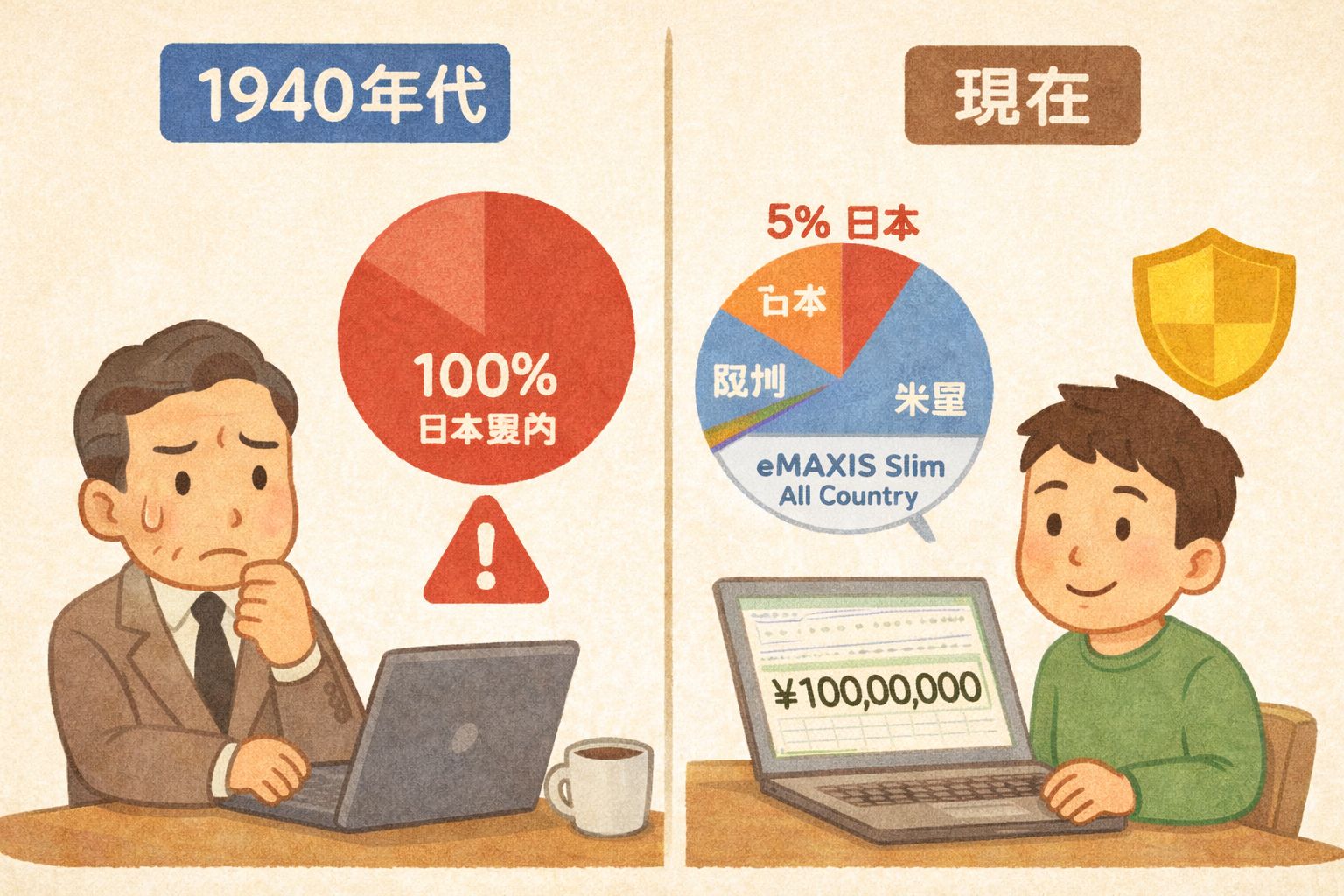

Why Japan's Historical Disasters Don't Apply to You

When you read international SWR research, you'll encounter a frightening statistic: Japan's worst-case safe withdrawal rate was just 0.47%. A retiree in 1940 investing only in Japanese stocks and bonds would have been wiped out by wartime destruction and post-war hyperinflation.

But that research assumed 100% domestic Japanese investments. That investor was:

100% concentrated in Japanese equities and bonds

100% exposed to wartime destruction and hyperinflation

0% internationally diversified

Your eMAXIS Slim All Country portfolio is fundamentally different:

Only ~5-6% Japan exposure

~95% international (including ~65% US)

True global diversification across 47 countries

Spread across multiple currencies!

From a Japanese perspective, you're maximally internationally diversified. Recent research by Cederburg, Anarkulova, and O'Doherty at the University of Arizona found that increasing international diversification to 90% raises safe withdrawal rates to approximately 3.0%. At 95% international (your ACWI), you're at the upper bound of that benefit.

The trade-off: Currency volatility. Your portfolio is ~95% denominated in non-yen currencies, but you see yen values. Short-term, this creates volatility (your 14.5% returns included ~5% from yen depreciation). Long-term, this diversification protects against any single country's collapse—including Japan's.

There's an elegant hedge built into this structure: if Japan's economy struggles and the yen weakens, your internationally-denominated portfolio increases in yen terms, preserving purchasing power exactly when you need it most.

Why 14.5% Doesn't Mean 14.5%

My wife came back to the kitchen around midnight. I was still at the table.

"What are you doing?" she asked.

"Figuring out why our eMAXIS returns don't matter as much as I thought."

She sat down. "Explain."

Here's what I showed her:

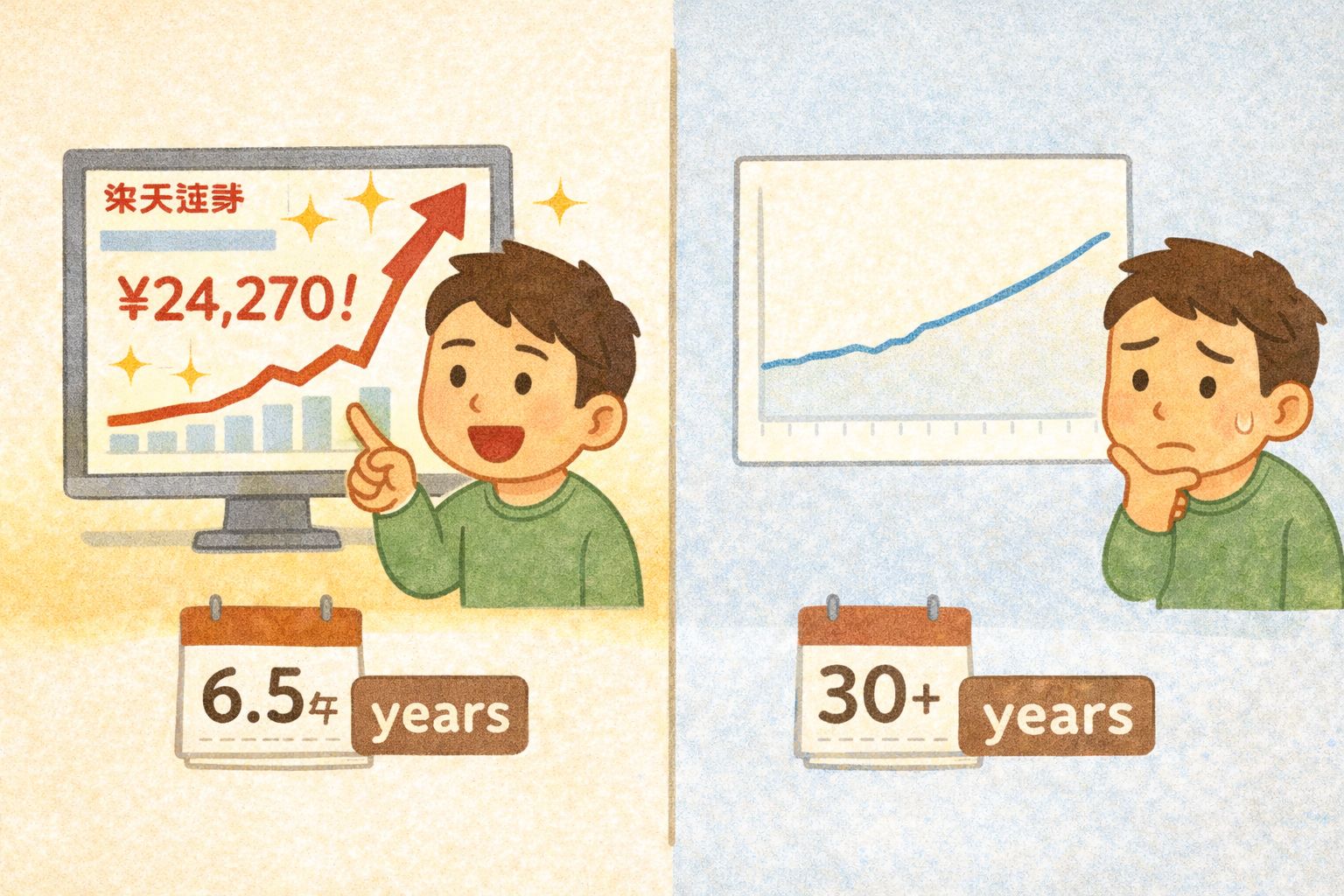

Our eMAXIS Slim All Country portfolio has returned about 143% since October 2018. That's ¥10,000 per unit growing to ¥24,270 by April 2025, according to the official MUFG fund reports. Roughly 14.5% annualized.

My Rakuten Securities account shows yen. When I check my balance, I see yen gains. My portfolio is denominated in yen. So why am I planning with 5% returns instead of 14.5%?

Because 6.5 years is not 40 years.

The 14.5% includes two major tailwinds that won't last forever:

First: An exceptional growth market. From October 2018 to April 2025, global equities went through one of the strongest runs in history. Central banks flooded markets with liquidity. Tech stocks soared. Earnings grew. This was not a normal 6.5-year period.

Second: Significant yen depreciation. The yen went from about ¥112 per dollar in late 2018 to around ¥150 today. That's a 34% decline. For a yen-denominated fund holding global assets, currency depreciation adds directly to returns. When the dollar strengthens, my yen-denominated eMAXIS units are worth more yen.

That currency move alone added roughly 5-6% annually to my yen returns. But the yen won't depreciate forever. If it strengthens back to ¥120 per dollar, my yen returns drop even if global markets rise.

The 30-year picture is more sobering. The MSCI All Country World Index, which eMAXIS tracks, has returned about 8.3% annualized in USD over 30 years. After US inflation of roughly 2.8%, that's about 5.5% real in dollar terms.

Here's how I think about it now:

What you see | Rate | Why it's that number |

|---|---|---|

Recent eMAXIS performance | 14.5%/year | Bull market plus yen weakness |

30-year MSCI ACWI nominal USD | 8.3%/year | Long-term global equity average |

30-year real return USD | ~5.5%/year | After US inflation |

What I plan with (yen, real) | 5%/year | Conservative, no currency bets |

My wife studied the table. "So you're ignoring the 14.5% completely?"

"Not ignoring," I said. "Just not betting our retirement on it continuing."

The CAPE Problem

There's another reason I'm using 5% instead of 8% or 10%: current valuations.

The CAPE ratio (Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings) measures how expensive the market is relative to 10 years of inflation-adjusted earnings. The historical median is around 16. Today, it's hovering near 40.

Every historical failure of the 4% rule happened when someone retired with CAPE above 20. We're at double that.

High CAPE doesn't mean the market will crash tomorrow. But it does mean future returns are likely to be lower than historical averages. When you buy stocks at high prices relative to earnings, your future returns compress.

Big ERN's research shows this clearly. Starting CAPE is one of the strongest predictors of safe withdrawal rates. High CAPE at retirement? Use a lower withdrawal rate. Low CAPE? You have more cushion.

At CAPE 40, I'm not comfortable with 4%. With Lily's future on the line, I'd rather use 3.5% and be pleasantly surprised by excess wealth than use 4% and run out of money at 75.

What This Means in Real Yen

The math changed my FIRE number completely.

Old calculation (American FIRE blogs):

Annual expenses: ¥4 million

Withdrawal rate: 4%

FIRE number: ¥4M ÷ 0.04 = ¥100 million

New calculation (Big ERN research, Japan context):

Annual expenses: ¥4 million

Withdrawal rate: 3.5% (conservative for current CAPE)

FIRE number: ¥4M ÷ 0.035 = ¥114 million

💡 This might seem like a lot, and it is, but you do not need to deposit 114 million to retire, we will revisit compound interest which does the heavy lifting!

But wait. There's a massive Japan-specific factor I haven't mentioned yet: pensions.

My wife's question that started this whole recalculation: "Did you remember we'll both get pensions at 65?"

I hadn't. At least not properly. I'd vaguely acknowledged pensions existed but never integrated them into my FIRE math.

That integration changes everything. But it's complex enough that it deserves its own explanation.

Next week, I'll show you exactly how Japanese pensions reduce the FIRE number by ¥20-40 million depending on your employment history. The math is specific to Japan, and understanding it changed everything about when we can actually retire.

📋 This Week's Actions

Before next week's newsletter on pension integration, get clarity on your own numbers:

Calculate your real eMAXIS returns: Log into Rakuten Securities or SBI and check your actual annualized return since you started. Compare it to 30-year MSCI ACWI data (~8.3% nominal USD). Are you planning with recent numbers or long-term data?

Pull your Nenkin Net projection: Log into nenkin-net.mhlw.go.jp (if you haven't registered, you can request a paper statement via Nenkin Office or use you My Number Card). You'll need these numbers for next week's pension integration math.

Recalculate your base FIRE number: Take your annual expenses in yen and divide by 0.035 (3.5% withdrawal rate). This is your pre-pension FIRE target. Write it down. Next week we'll adjust it for pension income.

That Thursday night at the kitchen table, I realized I'd been planning my retirement with American blog assumptions and recent bull market data. Neither applied to my actual situation: a 40-50 year retirement horizon in Japan with a yen-denominated global equity portfolio during historically high valuations.

The shift from 4% to 3.5% withdrawal feels conservative. Maybe it is. But sequence of returns risk isn't theoretical. The 1966 retiree proved that. And with CAPE at 40, I'm not betting Lily's financial security on continued exceptional returns.

The 5% real return assumption protects against currency reversal, valuation compression, and sequence risk. It doesn't assume the 2018-2025 bull market continues. It uses 30+ years of data instead of 6.5. And it aligns with Big ERN's research for long-horizon early retirement.

Next week: How Japanese pensions change the entire calculation. (Hint: Most dual-income couples need ¥30-40 million less than they think.) Part 4 will show you exactly how to automate the withdrawals with 定期売却サービス.

P.S.

Got questions about your own FIRE number calculation? Reply to this email. If I see patterns in the questions, I'll address them in a future newsletter.

📚 Further Reading & Sources

The research behind this newsletter draws from peer-reviewed academic studies and rigorous financial analysis. Here are the primary sources:

Safe Withdrawal Rate Research:

Big ERN's Safe Withdrawal Rate Series – The most comprehensive analysis of withdrawal rates for early retirement. Part 3 covers the "1 in 3 failure" finding for 60-year horizons; Part 18 covers CAPE-based adjustments.

Wade Pfau: "An International Perspective on Safe Withdrawal Rates" (PDF) – The landmark study examining 109 years of data across 17 countries. Source for Japan's 0.47% historical SWR and the global perspective on the 4% rule.

Cederburg et al.: "The Safe Withdrawal Rate: Evidence from a Broad Sample of Developed Markets" – Published in Journal of Pension Economics & Finance (2025). Found global SWR of 2.26% for 5% failure rate; 3.02% with 90% international diversification.

Cederburg et al.: "Beyond the Status Quo: A Critical Assessment of Lifecycle Investment Advice" – The paper arguing for 100% equities with 33/67 domestic/international split throughout life.

CAPE and Valuation:

Current Shiller CAPE Ratio – Live tracking of the cyclically-adjusted P/E ratio. Historical median ~16; currently ~40.

Michael Kitces on CAPE-Based Withdrawal Rates – Explains why starting valuations matter more than average returns.

Japan-Specific Context:

eMAXIS Slim All Country Fund Reports – Official MUFG performance data and expense ratios.

Podcasts for Deep Dives:

Rational Reminder Episode 284: Prof. Scott Cederburg – Direct interview with the researcher on lifecycle investing and international diversification.

Rational Reminder Episode 281: Safe Withdrawal Rates Discussion – Detailed breakdown of the global SWR research.

Disclaimer: This newsletter shares my personal financial journey and research for educational purposes only. I'm not a licensed financial advisor. The calculations and frameworks I share are based on my interpretation of publicly available research and my own situation in Japan. Your situation is different. Before making major financial decisions, consider consulting with a qualified financial advisor familiar with Japanese tax and pension systems. Past returns (whether 14.5% or 8%) do not guarantee future results. All investing involves risk.

Stay Wealthy

Jason

Building wealth for English-speaking permanent residents in Japan, one story at a time.